|

The Northern Altiplano

I Hit the Pedals

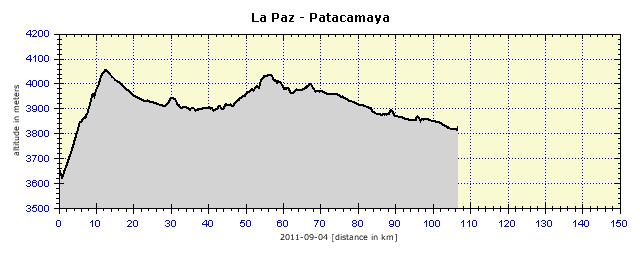

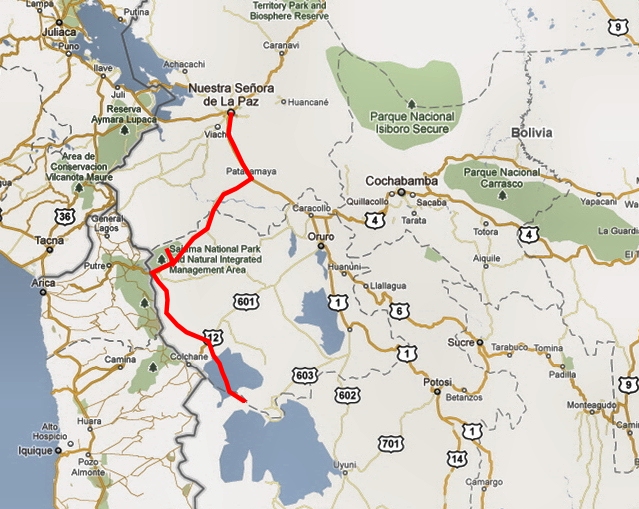

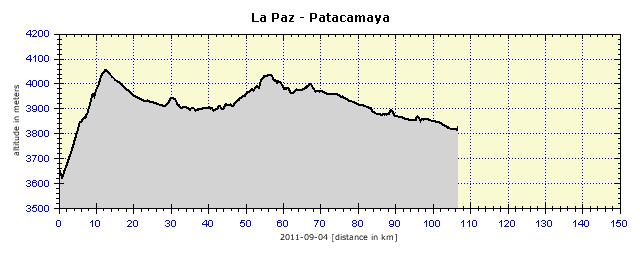

After ten days’ acclimatization to the local altitude, I finally set off on a Sunday morning. Because I wanted to find accommodation that night in Patacamaya, over 100 kilometers away, I got up early. By 7.15 a.m. I was seated on my bike in front of the hostel. Traffic was minimal, however one Colectivo almost swept me off the bike at a crossroads - I was going straight, he was turning right and heading straight for me. Maybe he hadn't seen me, but I somehow managed to avoid the collision.

Climbing up to El Alto was quite challenging. It was tough going, after almost 14 days of not cycling. It was better on the Altiplano, where the breeze quite often blew from behind. However, I was becoming aware of just what lay ahead of me. It was not going to be easy. A blazing sun, a wind which dried the skin, lips and inside of the mouth, and, added to all this, the undulating terrain. Moreover, I felt a pressure in my lungs all the way, probably a result of 20 years of passionate pipe and cigar smoking.

At times, I had fits of coughing. It was no fun. I was quite annoyed that I wasn’t able to drink from my new Smart Tube (a tube attached to a PET bottle), although it had worked just fine at home. Sucking up water into the mouth simply required so much strength that it was impossible to drink. The problem was caused by the low pressure at high altitude, for which the air valve in the screw top of the bottle was not adapted. When I removed the valve, although I was then able to drink, no water remained in the tube, so I always had to suck it up from the bottom. I decided to leave drinking for the lowlands. I also finished chewing the coca leaves, which had been left over after the visit to the mines in Potosí, and came to the conclusion that they had helped. I decided that, when next I saw any on a market, I would stock up again. I just hoped that the pain in my chest would pass off in the coming days.

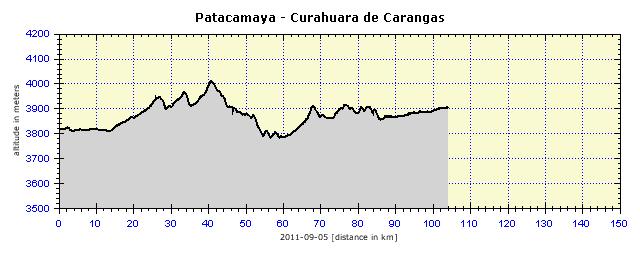

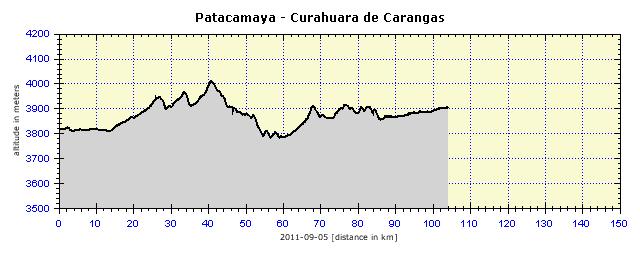

The next day the pain in my chest eased off. I was not even coughing, but was exhausted and found it quite a struggle to get those 100 kilometers under my belt. The route was like cycling from one deep hollow to the next, only with rather steep edges. In the afternoon, it started to get interesting—the distant red landscape with traces of white salt and the number of burial chullpas along the road. The ubiquitous untied dogs chased me in every village, increasing my average cycling speed, as they forced me to speed up. Because of them, I had bought a tear gas spray in La Paz, but I was not yet forced to use it.

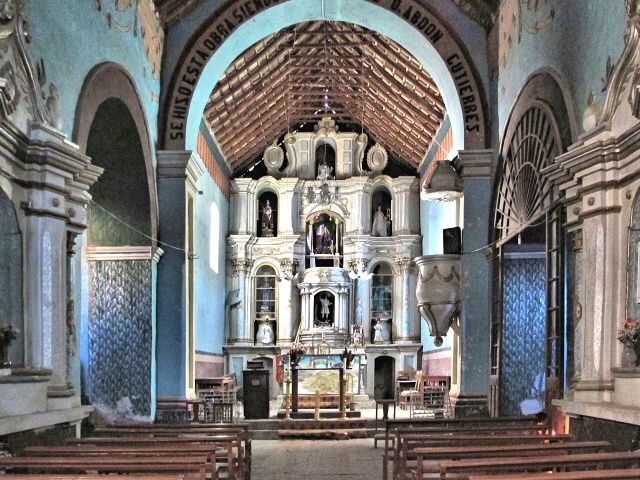

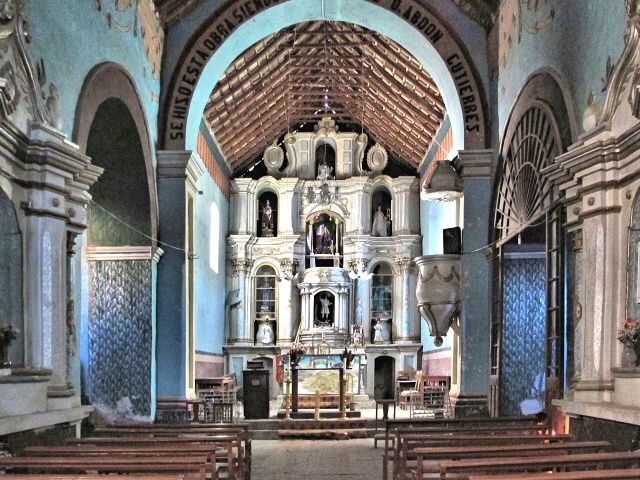

I almost missed my destination of Curahuara de Carangas, because it was shown on my map as being on a highway, while it is actually 5 kilometers off the highway. The biggest attraction there is the local church, which has impressive Naivistic interior frescoes and is known as the “Sistine Chapel of the Altiplano”. It can only be seen with a Spanish guide for 5 Boliviano, which of course I paid. The guidebook claims that it is possible to take photos of the interior for another 5 Boliviano, but the Spanish guide denied this. What a pity! The interior frescoes are really impressive and rather weird – for example, there is not a fish on the plate in the painting of the Last Supper, but a four-legged animal, and so on.

The hostel was quite basic. A couple of Danish students, who had cycled from La Paz in a leisurely six days (I managed this in two), were also staying there. Before that, they’d been on a ten-day Spanish course in La Paz, so were well acclimatized. It was their first cycling trip, and they wanted to go on the same route as I to San Pedro de Atacama. We went to the pub together for a meal and compared our maps. The differences and inconsistencies between the maps were so great that they eventually decided to take the bus to Arica in Chile, buy a GPS navigation device and come back.

[Near Patacamaya] A Bolivian village

[Near Patacamaya] Rugged landscape. The white substance is not snow, but salt

[Near Puerte Japones] Chullpas - mausoleums for mummified relics of famous people

[Cuarhuara de Carangas] A church, called the Sistine Chapel of the Altiplano, with unique naivistic interior decoration. Unfortunately photography of the interior was prohibited

Man Proposes, the Weather Disposes

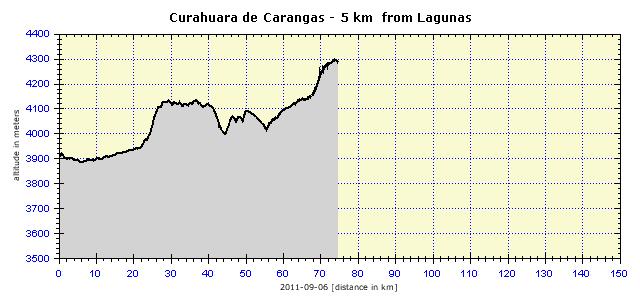

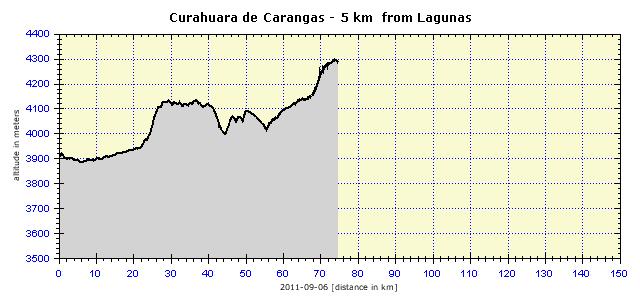

In the morning, I headed out before 8 am, with one of the Danish students managing, sleepy-eyed, to wave me goodbye. At first all went well, cycling around many pastures with llamas grazing in them—a pastoral idyll. But then the quite steep pushes uphill began. It immediately became clear that, at 4,000 meters above sea level, it is much tougher going than in the lowlands, even if one is acclimatized. The heart just has to get a given volume of oxygen circulating through the system, so when there is less of it in the atmosphere, it must pump harder. And that makes one pretty tired.

But I was bothered mostly by the wind, whirling around my head all day long, drying up all the mucosa, so that the inside of my mouth was continuously dry. Even after drinking, it was immediately dry again. Eventually, I pulled a ski mask over my mouth and nose, which eased it a bit. The chewing of coca leaves also helped significantly. I always had a bag of them in my jacket pocket and regularly inserted a small quantity between my teeth and gums as a “bago”.

Originally I was heading for the village of Sajama, which is the center of the National Park with the same name, the oldest in Bolivia. About 20 kilometers from my destination, such an incredibly strong headwind arose that it became a problem even to push the bike. Riding it was simply out of the question. The wind seemed to blow directly into my lungs, clogging me up. I had to tilt my head sideways, merely to get a slight bit of relief. It was clear to me that I would have to sleep in the tent that night.

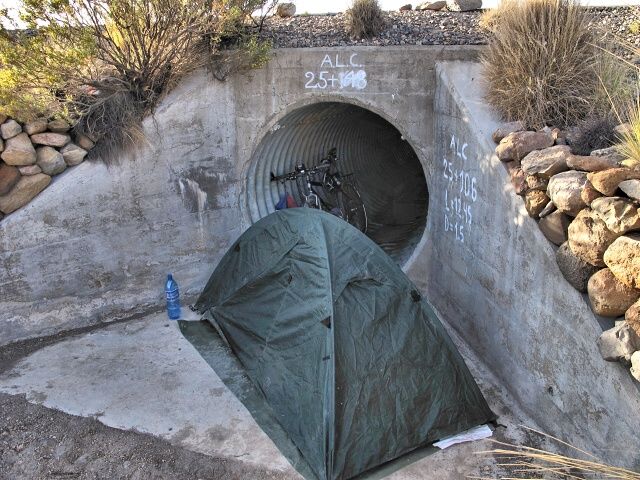

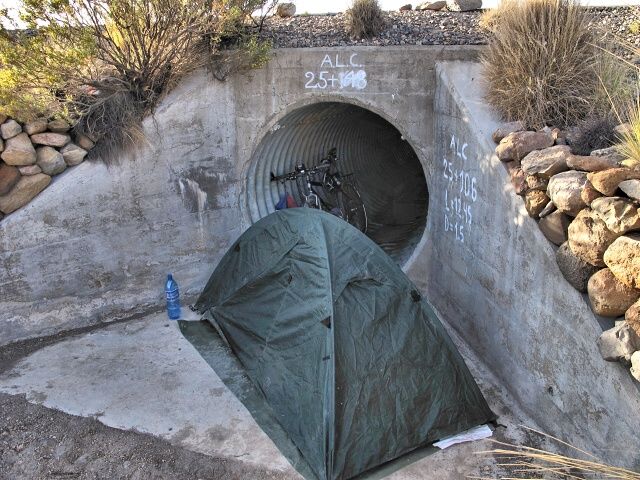

However, it is not possible to erect a tent in such a gale. The main priority was to find some shelter. The surrounding landscape was a plain, covered with 30-cm tall grass, so I had to look for something artificial. I finally found a roadside culvert which was sunk into the ground. There was almost no wind blowing in there. It did not look like rain, so I risked setting up my tent on the concrete in front of the culvert, hiding the bike in the drainpipe. I wrapped myself up warmly in anticipation of the cold, but during the night I had to throw off some clothes. At an altitude of about 4,000 meters, the lowest temperature in the tent was 8°C and my 800-gram down sleeping bag and self-inflating groundsheet coped very easily.

[Near Cuahuara de Carangas] Impressive Sajama volcano; the highest mountain of Bolivia - 6542 m

[Near Lagunas] The first night in the tent here – the only sheltered place that saved me from the terrible wind

Penal Trip

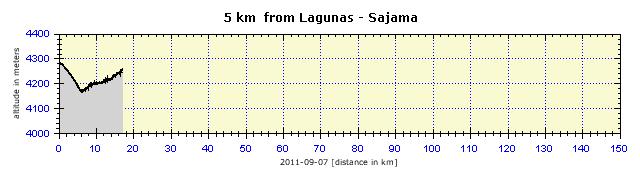

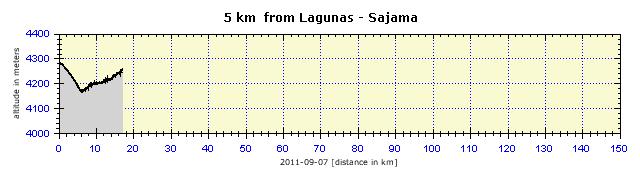

In the morning, quite hungry and thirsty, I cycled about 5 kilometers before reaching the turn-off to the village of Sajama. Another 3 kilometers along the asphalt road would have taken me to Lagunas, where I would have liked to eat. However, a strong wind had come up and I didn’t want to continue cycling in the wind on the paved road. After all, the village of Sajama was only 11 kilometers away. To my horror, I ended up cycling, or rather walking, for more than two hours. The road surface was actually a 10-cm layer of sand with, in the ruts left by trucks, only a 3-cm layer of sand remaining. It was really tough cycling on this, with a fully loaded bike. I estimate that I cycled about 3 kilometers and pushed the bike for the remaining 8 kilometers.

I paid the entry fee of 30 Bol. (approx. 4 USD), to the National Park (and village) and checked in to the hostel. I wanted to take a shower, which I badly needed. Another disaster! The electricity was off in the entire village and was not turned on again until the evening. The hostel started up a generator at dusk which was not sufficient for the shower. But above all, I was starving.

The locals must have had a good laugh at me, as I wandered around the square visiting several cocinas (one cook, a small room with a table, gas cooker and containers with home-cooked food). I ate something in each one - soup, chicken, llama. After finally having my fill, I wanted to see the area of geysers 8 kilometers away. A Bolivian family in a passing car offered me a ride. They were going to boil their eggs in the geysers. I wandered around the geyser site, had a good soak in the reasonably warm water, warmed up and washed myself thoroughly. Providentially, I had taken a towel along with me.

[Road to Sajama village] Covered and protected from wind and sun; tough road covered with sand

[Near Sajama] Ruins of a church

[Sajama] Sajama volcano keeps watch over the village with the same name

[Sajama] Llama getting ready to sleep in the middle of a village

[Sajama] Geothermal area with mountain geysers

[Sajama] Geothermal area with mountain geysers

[Sajama] The Bolivian family who took me to the geysers

Folk Festival, alas, in Total Darkness

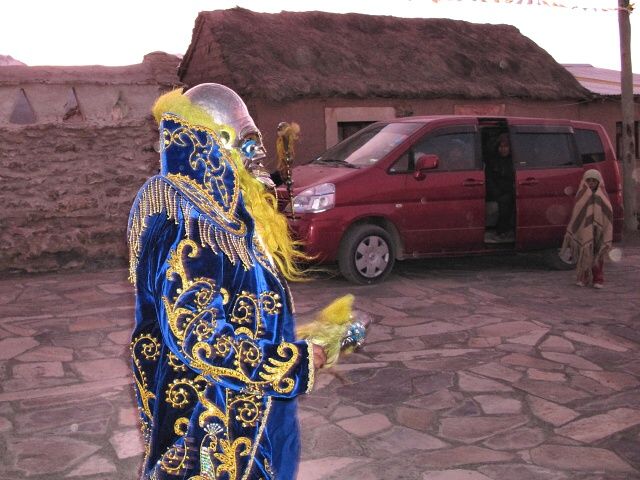

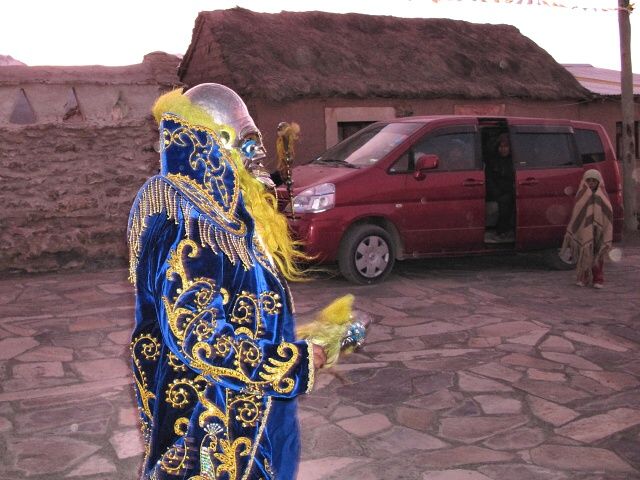

A huge dance celebration was being prepared for the evening. In the afternoon, a football match had been held. With about 5 cm of local volcanic ash on the field, the game must have been very physically demanding, although the players seemed oblivious of this fact. In the evening, just before dusk, music was heard in front of the church. Dancers in exquisitely decorated costumes appeared and started to dance vigorously. Powerful rhythms, exciting dancers, it would have been an amazing spectacle if only it were visible! Well, of course, there were firecrackers and fireworks. However, after the experience at Sucre, I tried to remain at a respectful distance from those. One hole in my jacket was quite enough for me. They danced the night away. Even at 3 a.m., I could still hear the music. And the next day, before 8 a.m., they started up again, but already slightly wearily after all the alcohol consumed. By the way, in my sandals and summer clothes, I was suffering from the cold. The village was 4,250 meters above sea level and the wind was blowing in gusts and blasts...

[Sajama] Dancers and their “rehearsal” in a pub starting already at lunchtime

[Sajama] Costumes for the dance festival were spectacular

[Sajamay] Masked dancers walking around the village square

[Sajama] The dancing was impressive, but we didn't see much as there was an electricity failure in the entire village

[Sajama] Costumed women twirling their wide skirts

¨

[Sajama] Next day, it continued already from early morning

[Sajama] A memorable photo of one of the dance companies

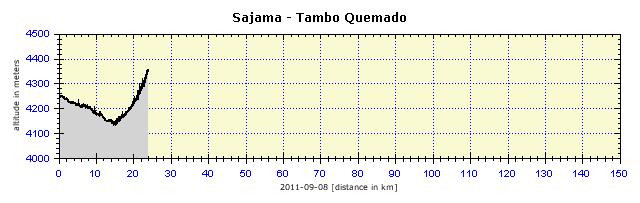

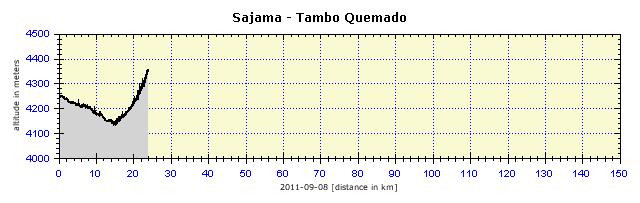

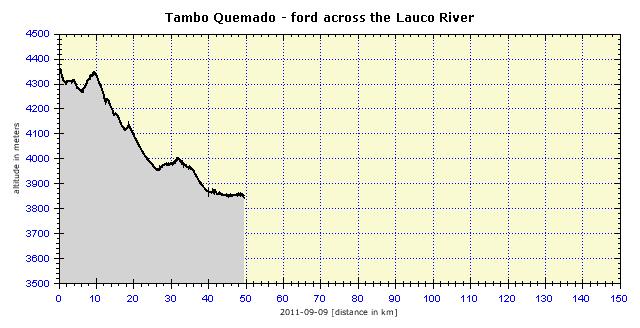

The return to the main road was better. It was downhill, after all, and, more importantly, the previous day’s headwind was absent. The two approaching figures of cyclists coming towards me turned out to be the Danish students, as I had suspected. They had taken a day’s break, because the 60 kilometers of the previous day had apparently proved too much for them. Mike, in particular, was complaining that his butt and legs were aching. I saw the first lagoon with flamingos –where else, but near the town of Lagunas? Then I climbed steadily along the main road to the border crossing at Tambo Quemado. A wind with the strength of a small storm was blowing directly into my nostrils. So I pushed the bike the last kilometer uphill, also with difficulty. It is interesting how a strong wind negatively impacts the psyche. The buzzing and humming around the head is simply annoying.

[Road to Sajama] Me in front, Sajama Volcano in the background

[Road to Sajama] I again met Mika and Cyril, friendly Danish students

[Road to Sajama] Herds of llamas feed on the Sajama hillside

Ugly Tambo Quemado

My main intention was to wash my clothes, take a shower and generally prepare myself for the upcoming journey into the wilderness. But, no such luck! Before crossing into Chile there were at least eight accommodation facilities (alojamiento), none of which had any vacancies. So I began a second round of negotiations. The only success I had was being bitten by a dog on whose paw I had stepped in the half-light. Fortunately, he did not bite through the fabric, so there was no contamination by saliva. However, slightly bleeding wounds remained on my thighs. So I tried harder and finally convinced one old woman to give me a room for the night. I was given a tiny, dark, windowless room on the 3rd floor. I had to drag everything, including the bicycle up the three floors on the outside stairs without any railings. The electricity reputedly did not function at night, so I was left in the dark until morning. This meant that there was also no hot water in the communal shower. My forehead lamp started to run out of battery. Naturally, nobody in the village sold any batteries. It was impossible to be outdoors, wind, cold and nothing interesting besides the many smelly trucks waiting for clearance. So I promptly solved the problem. At 5 p.m. I ate a hearty meal, bought a bottle of local red wine, downed half of it and crawled into my sleeping bag, where I dozed until morning.

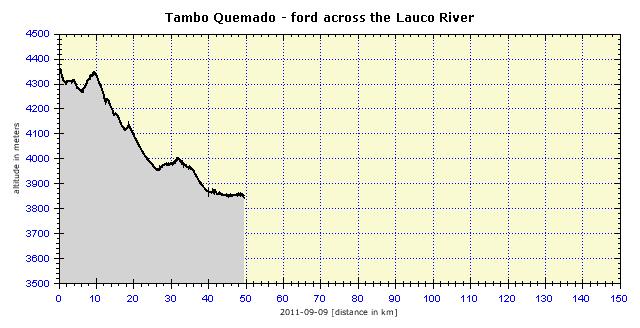

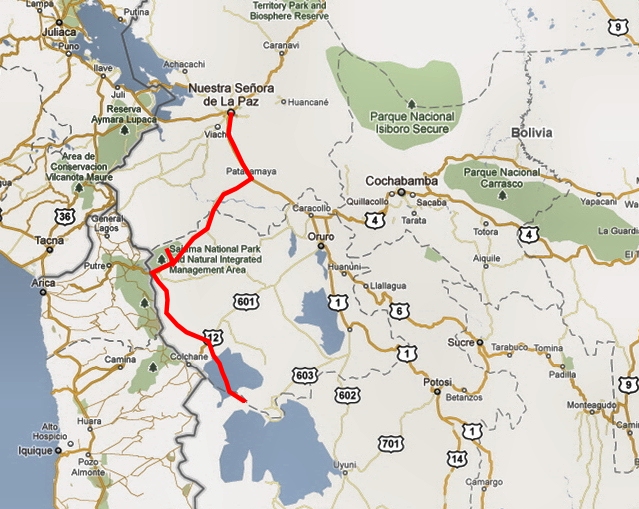

Don’t go to Altiplano without GPS Navigation

I bade farewell to the paved road and cycled on dusty roads that gradually changed into field roads or dirt tracks. There are many such dirt roads in the countryside, often leading parallel to one another for several kilometers before parting. Now, which road was the right one? There was no one to ask, I only came across about two cars during the whole day. Signboards are not common here, I saw about four of those in three days. There are small garrisons in the villages (of about five to ten soldiers) which would be a reliable source of information in the Czech Republic. Not so in Bolivia – the soldiers did not know the name of a village 20 kilometers from their garrison. They looked at the map as if seeing it for the first time in their lives. And in one garrison, an English-speaking officer brought a copy of a sketch map (that is, a few lines on paper, no printed map), to explain to me that the place I was asking about simply and clearly did not exist. I think that, without GPS, I would have wandered around there for several days on roads buried waist-deep in the sand. Even with the GPS, it was sometimes difficult, especially to believe that the relevant narrow track one was on was precisely the right one.

[Nogachi] Sometimes it was necessary to cross the water

[Near Rio Lauca] A normal road; this one was a bit better, with only a thin layer of sand

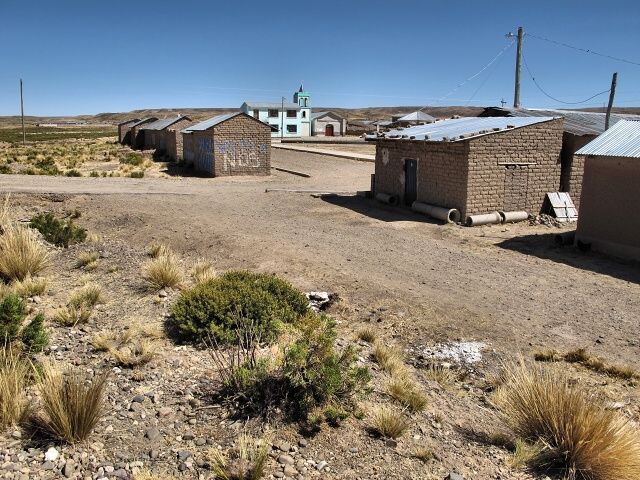

[NearJulo] A mountain village

[Near Julo] Llamas were curious, they usually don´t see much traffic here

[Near Julo] After a cheerful chat, this local cyclist allowed me to take his photo (free of charge)

[Julo] Each village has a Catholic church, plus one less magnificent temple for less popular religions

A Swiss cyclist who was travelling in the opposite direction had a very detailed map of that area, with directions in Cyrillic. He had bought it in Germany before the trip and had used it to cycle in a circle from Chilean Calama. Although he tried to follow only the bigger roads, he was still having major navigational problems.

[Near Julo] I passed a Swiss colleague (going the other way). Apart from this encounter, I saw only two cars the entire day

Food and Accommodation – Zero

It was a problem to find anyone in the villages. Everybody seemed be out with the animals on the pastures. When I finally encountered somebody, usually there was nothing to buy in the village. Sometimes there was a store in a shed, where the main stock was sweetened drinks and biscuits. Bottled water was not available. I took some water from the soldiers but, to be safe, ran it through a filter – my Steri Pen produces one liter of water in 90 seconds and one only needs to push the button, no exhausting pumping. I was offered accommodation only once, in Macaya, where an old woman managing a store like those mentioned above, agreed that I could sleep in the room with her and her granddaughter. When I saw the dirty den, straw mattresses on the floor instead of beds, I politely thanked them and quickly left. Thanks to the GPS, I knew that the road crossed the Lauca River after about 10 kilometers There was no bridge, so I crossed the river in the evening to avoid getting wet the next morning. I found a little elevated bank which shielded me somewhat from the wind. I slept peacefully in my tent, without the risk of some blood-sucking lice, which was a real possibility had I accepted the offer of the dirty den.

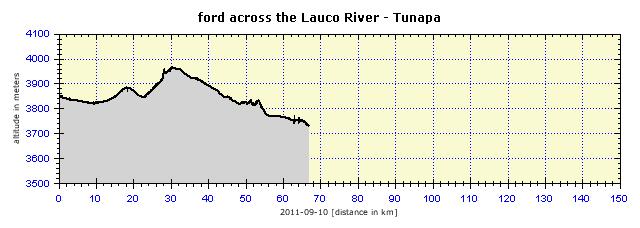

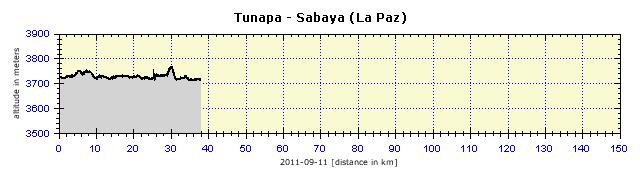

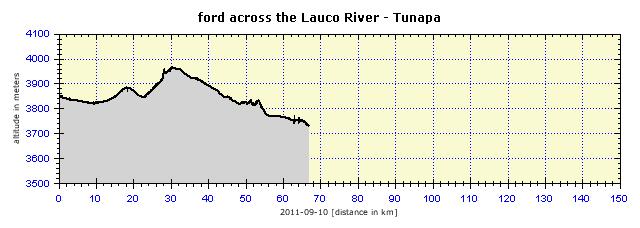

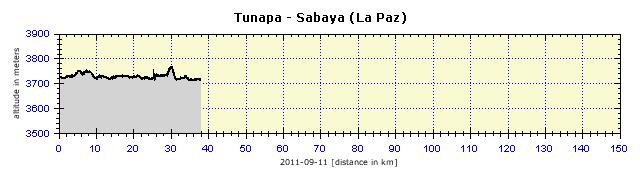

The next day I wanted to cycle at least to Tunapa village, buy some food there and maybe even sleep over in a bed. I labored uphill for half the day. After that, a fairly decent flat road followed, but I was troubled by the wind again. The final 12 kilometers were on a field road covered with thick sand. Had I not had the GPS navigation, I would not have believed that it was the correct route. I arrived in Tunapo in the dark, with all the houses steeped in darkness. Were it not for the street lighting, I would have thought that the village was completely deserted. On the square, I knocked on the door of a house from which I heard soft music coming. The man of the house told me that there was no store in the village, and of course no accommodation. But that a tap with running - supposedly drinking - water was situated in a side street. I made my bed right on the square, made soup and tea and conveniently washed myself at the tap in the dark. In the morning, I was brought a packet of biscuits from the house, which I refused with thanks, because I saw their small children hungrily peering at it. These were the only people I saw in Tunapa. Otherwise, it was deserted and desolate.

[Tunapa] There was nothing in the little town – no food, no lodging, so I “made my bed” on the square

[Near Tunapa] A mountain village

[Near Sabaya] Chullpas – burial mounds

It’s Freezing at Night: No Problem!

I was really excited about the Koteka 500 sleeping bag from Sir Joseph. It weighed only 800 grams and when I took it out of the cover, it was a thin limp cloth. It had to be thoroughly shaken until the feathers recovered. After I crawled into it, it was suddenly inflated by my warmth and heated up beautifully. In combination with a self-inflating groundsheet (even though it was a child’s and only 120 cm long) and the tent, it was no problem for me to sleep outdoors in the local freezing nights as if on a bed of roses. In the morning, the water in the PET bottle left outside was frozen solid, but the temperature in the tent was still a decent 5 degrees above zero. Then I would have breakfast consisting of a tin of sardines and a bread roll, fill myself up with water which I had left in the tent overnight, so that it was not frozen –and that was sufficient for the day of cycling ahead. In the evening, if I had enough water left over, I would make instant soup from a packet. And of course, I compensated for this deficit every few days whenever possible. Then the locals would stare at me and wonder why I was eating three times as much as they were.

Crunch, Crunch – went the Front Pannier Rack

I was about 10 kilometers from the town of Sabaya, when a sudden crunching sound was heard. The front right bag fell down and I heard one of the most horrific sounds, just as when the spoke of a wheel strikes metal. The support of the carrier had broken and this was a real problem. I flung the bag on to the rear carrier, fixed the front pannier rack with tightening tape and made it into the town. First I wanted to check the Internet to see if I had a chance of buying a new carrier in La Paz. There was no Internet. The last bus to Oruro had left at 5 p.m. Buses from Chile, which also passed through the town, did not stop there. I found some accommodation, left my possessions there and decided to go by bus to the 450-kilometer distant La Paz to try to buy a new carrier. If I could not succeed, I would have to have it repaired somewhere. This would be no easy task, as it was a Dural, which is difficult to weld.

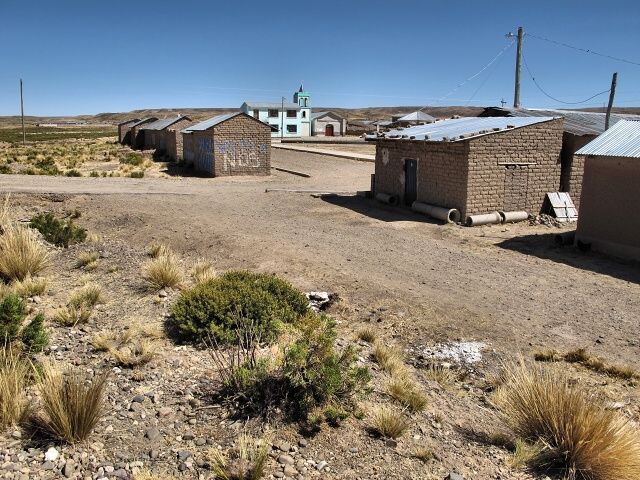

[Sabaya] The most beautiful part of the small town, which is situated on the dusty international road to Chile

[Sabaya] The statue of an Indian with disproportional arms; the left one has a bit broken off

More Buses, More Fun

Up until then, I had used buses of the highest class (cama), but this would probably not be the case now. A ramshackle bus arrived, a bunch of equally shabbily dressed men stormed out. While still on the run, they were opening their flies and urinating in broad daylight in the middle of the town in any available spot. Some of them targeted the wheels of the bus, less hardened individuals ran into side streets. There was no free seat, but I was allowed to board. I did not feel like standing for the four hours to Oruro, but there was no other option. As the only foreigner, I stuck out like a sore thumb. Soon a good-natured bunch of guys swooped on me. They were part of a band returning from a four-day festival, all as happy as larks. They started forcing a variety of drinks on me. If they’d had their way, I would have been quite groggy after half an hour. Fortunately, I managed to pour most of it, little by little, on to the bus floor, unnoticed by them. This I was doing deliberately, and they were doing the same, unintentionally. But they were a nice bunch, and eventually let me sit down. So the journey in the stench and turmoil passed by fairly quickly. In Oruro, I changed to the La Paz bus, the terminus of which I reached at 1.30 a.m. As I wanted to get some sleep, I had taken my sleeping bag along. The bus station was closed and would only open at 3.30 a.m. What next? I tried to walk around the outside of the station, but that soon bored me. I decided to look for an all-night pub for some food and shelter. I walked about 2 kilometers to the city center, before noticing that I was being followed by two guys. Immediately I flagged a taxi, returned to the terminus and survived the rest of the night there, bored but safe. After the bus station opened, I grabbed a bench, got into my sleeping bag and slept there until 7.30 a.m., when a local policeman woke me, saying I was not allowed to sleep there any longer.

First I went to the Internet, checked my E-mail and found where I could get the best information on the purchase of cycling equipment. The best choice was “Gravity Assisted Mountain Biking”, situated in the city center. They spoke English, but what they said did not please me. According to them, I would not find the carrier in La Paz (by the way, even in Prague this would probably have been a problem). The best and, according to them, also the cheapest solution, was to have it custom-made. They gave me an address in La Paz, to which I could take the bike and carrier and tell them to do exactly this. It would perhaps be heavier, made of steel, but they would produce it and it would work. To be sure, I also toured all the bike stores. “Delantero portaequipajes” understood my needs, but did not have the carrier.

At 1 pm already, I headed back for Sabaya. I only bought WD for cleaning the bicycle and a hat and gloves from Alpaca wool so as not to suffer from the cold unnecessarily. The catch came in Oruro. At the bus terminus, I found that there were only international buses to Chile, which were passing through Sabaya. But they beat about the bush, saying: “If we have any seats left, we’ll take you, but the price is 100 Bol.” (from Oruro to Sabaya I had paid only 20 Bol.) It was clear to me that there had to be regular connections departing from another stop. But nobody at that terminus was willing or able to inform me. There were many hawkers hanging around in the side streets near the terminus, so I made my rounds of them. They sent me to the other end of this city of a quarter million inhabitants. It was no problem to travel by Colectivo for less than the equivalent of 20 US cents. There I found Sabaya Transport, bought a ticket for 25 Bol. and at 1 a.m. was back in bed in Sabaya.

Repair of the Pannier Rack

It was time for Plan B, the Repair. A mechanic was located right next to the hostel, but I was not optimistic about him. His premises consisted of a yard with four wrecked cars and one vice. I cleaned the dust and salt from the bike, greased it and with a heavy heart approached the repairman. I recalled Gibb River Road in Australia, where the front pannier rack had also been damaged. When I had bumped along to the only repair store on the 650-kilometer road, the repairman and owner of the store had informed me that he could not repair it and that I had to do it myself. But I digress. The mechanic was lying under one of the wrecks, but immediately showed some interest. It took him a while to orientate himself. Then he kept muttering “aluminum, aluminum”. It did not seem to me too appropriate at that moment to tell him that “Aluminum had moved to Humpolec”, as is the famous quote from an old Czech movie. We dismantled the carrier and he very deftly straightened it with several taps on the anvil. Then he wanted to weld with electricity, but this failed. He took out an oxyacetylene burner and I had to stop him, asking him first to remove the front wheel, otherwise he might have burned the front tire. He welded the aluminum and, after it had cooled, it looked really solid. I didn’t know how it would fare, but meanwhile I would stick to my original plan. I would not go straight to Chile, but would try the salt flats, hoping that the carrier would survive with me.

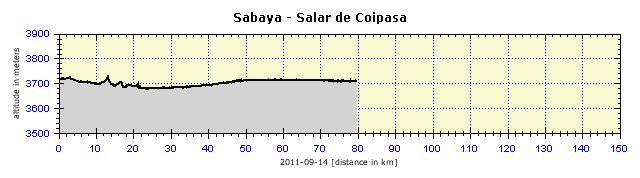

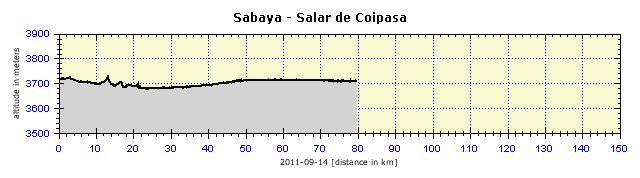

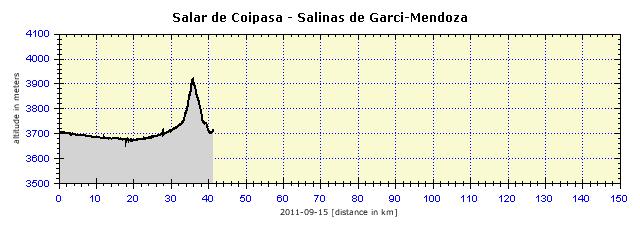

Coipasa Salt Flat

This is less popular than Salar de Uyuni. It is often partially flooded with water, which makes cycling on it more difficult. It can even be impassable in some areas and I was warned against it. The Swiss cyclist rather cycled around it, but I had to give it a go, of course. It started inconspicuously with a thin crust of salt, which sank beneath the wheels. A very strenuous ride. Then a solid layer of salt followed. If salt is more or less smooth, cycling is a pleasure and one feels as if on ice. However, the surface was often grooved with several centimeter-high “stalactites” and then it was hard work again and I failed to go faster than 10 kilometers per hour. Cycling in water was also interesting. In a depth of 5 to 10 centimeters, I could not stop, or I would have got my shoes completely soaked. Nevertheless, it offered magnificent views, the water reflecting the clouds and, after a while, I had the impression that I was actually floating in a surreal white and blue landscape between heaven and earth. Only the splashing of the salt water brought me back to reality.

[Salar de Coipasa] The salt flat starts gradually with a thin salt crust

[Salar de Coipasa] Unlike Salar de Uyuni, Coipasa has many flooded areas and that´s why it is pretty dangerous here

I was absolutely alone on the vast salt flat. Several times in the distance, I saw a Jeep travelling along the edge of the plain. In the afternoon, I came across a pair of Russian motorcyclists with whom I had spoken the previous day in a Sabaya pub. We took some photos, chatted and they quickly disappeared over the horizon. After that, for several hours I literally battled with the rough terrain on which the bike leapt like a mountain goat. The worst predicament arose in the evening. I did not want to sleep directly on the salt, so I diligently moved towards the edge of the salt flat. However, the edge was separated from me by a 5-kilometer wide salt-water lagoon. The water was 5 to 15 cm deep, so I drenched my shoes and legs and bespattered the whole bike, before reaching the edge. I was pretty exhausted, but did not want to stop, as I did not want to soak my legs unnecessarily. I was worried that the terrain might decline and the depth of water would increase. Then I would have to return to the salt, sleep there and hope that it would be frozen in the morning (it was not). Fortunately the water remained shallow, so I finally cycled out of it and pitched my tent right on the edge of the flat and, totally exhausted, prepared for sleep.

[Salar de Coipasa] Cycling is partly idyllic, partly very exhausting and tough

[Salar de Coipasa] A Russian motorcyclist explains to me how they show the V-sign in Asia

[Salar de Coipasa] A couple of Russian motorcyclists

[Salar de Coipasa] Salt is sticking on the bike, it´s not at all good for it

[Salar de Coipasa] On the flat you can find ruts left by trucks filled with salt water

[Salar de Coipasa] Flooded parts of the salt flats are reminiscent of riding between heaven and earth

Salt, Salt Everywhere…

My legs were covered in salt spray up to the knees. My socks were so encrusted in dried salt that they resembled plaster casts and I could not remove them. Likewise, I had a problem undoing my shoe laces. I nearly wept to see my bike –totally covered in a 2-centimeter salt crust, with salted saddle bags, especially the front ones. I had no water to wash them with, only enough to drink and for the next day’s trip. I changed out of my clothes carefully in the tent, trying not to get salt into the sleeping bag, camera, GPS and so on. In the morning, I removed a large quantity of salt sediment by hand from the bike, using up almost half of the WD with which I sprayed the sensitive components.

[Salar de Coipasa] The night on the salt flat was easy

[Near Alcaya] When I found no road, I whizzed through the vegetation “following my nose”, pardon me, following my GPS

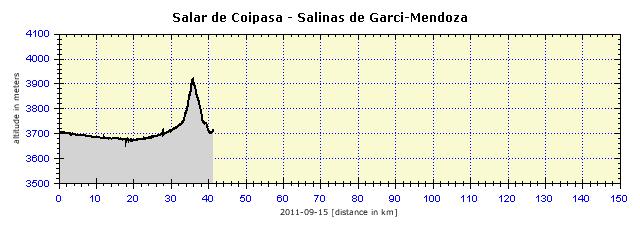

[Alcay] The climb up to Salinas de Garci-Mendoza is visible in the upper left hand corner

[Near Alcay] View of the distant Salar de Coipasa – white surface under the mountains in the background

[Near Alcay] View of Salinas de Garci-Mendoza from the other side; and a view of the Uyuni salt flat

I arrived in the town of Salinas de Garci-Mendoza and decided to stay over there. On the square I met an American cyclist, a young lad with an incredibly filthy bike. He had been to two local hostels to find that there was no available accommodation. (Hostel managers generally take fright when seeing a cyclist coated in dirt and refuse him accommodation). We found accommodation on the edge of the town, where I cleaned the bike and bags for two hours and washed my pants and socks. Only a thin layer of gray salt remained on the bike. Very good news – the welded carrier was holding up so far. In the evening the Russian motorcyclists arrived, smudged like pigs and completely exhausted. They looked at me in awe, wondering how I had got there from Salar de Coipas. When they had tried to get across the salt flat, they unfortunately got into deep water which ran into the exhaust pipes and their motorcycles broke down. They then had to push their bikes for several kilometers through deep water. What a horror! So I’d had a very lucky break the previous day!

And, in conclusion, a funny incident: I went to dine in the restaurant on the square, where I’d asked for accommodation several hours earlier and had been rejected. The proprietress asked me where I was staying and why I was not lodging at her establishment, as she always had free rooms and at a lower price and, besides, right in the city center. I explained to her that I was the cyclist who had wanted accommodation in the afternoon and whom she had rejected. “Yeah, it was absolutely overcrowded at that time!” she replied, at which we all had a good laugh. Indeed, clothes do make the man.

[Salinas de Garci-Mendoza] Interior of a local church

[Salinas de Garci-Mendoza] Fresco in the church

|