|

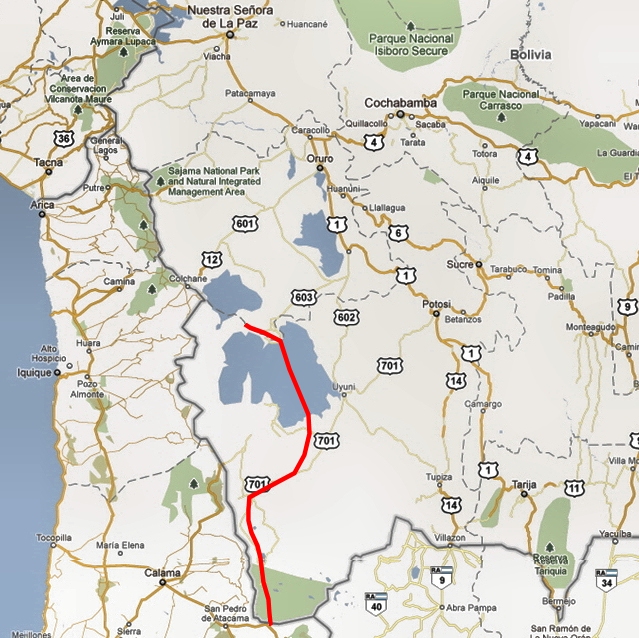

The Southern Altiplano

Salar de Uyuni

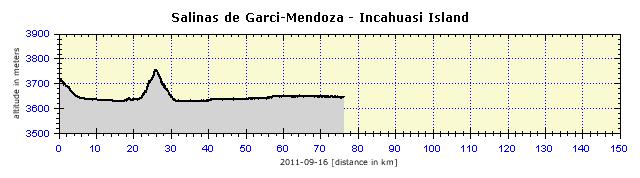

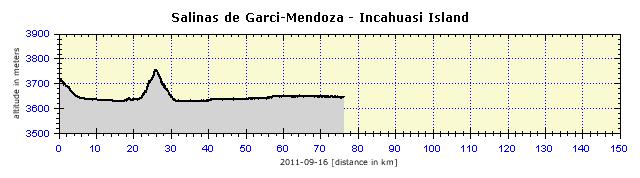

In the morning, making a beginner's error, instead of making purchases in Salinas, I left it for Jiriri where there is also a store. However, on the way, in Churacari, there was a slip road to Salar. One is only permitted to enter the road to Uyuni at specific spots. If I had done my shopping, I could have comfortably cycled on a flat road to Salar. Instead, I labored up the rocky hill and on the other side pushed my bike through sand drifts. Nevertheless, in Jiriri I bought water and biscuits in the "Posada de Luca" store. I asked what food they had and they said that the soup would be ready in ten minutes. It was delicious, I had two plates and they did not take any money for the soup, saying that a cyclist needed soup. Moreover, they stuffed some more biscuits and nuts into my pockets without charging me anything.

[Churacari] A village square

I Levitate, I Fly

The best route to Uyuni was near the edge, where the salt plain was nice and smooth. Towards the center, the plain increasingly resembled cycling on big cobblestones. The sun was beating down on to the salt which sparkled like deep-frozen snow. There was not a soul in sight. I tried to cycle, for example for five minutes with my eyes closed, testing whether I could keep a straight course – it was successful, the presumption that a blind person tends to move in a circle was not confirmed. The white bright light was so blinding that I thought it an ideal place for hallucinations. And so it was. My back began to itch severely and suddenly I was looking at myself from the height of 2 meters. I wondered why I was so hunchbacked on the bike. Then I plucked up the courage and slowly rose to about 50 meters, still watching myself from above. Up and down the movement was easy, but it was quite difficult to move from side to side. It was as if I was connected to a rubber rope and any deviation from the direction drew me back, directly above my physical appearance pedaling below me. I eased off, trying to ascend even higher, but it started to be unstable, like a good aircraft indicating by shaking that it is approaching the stalling speed. This lasted for about 20 minutes and then I slowly sank back on to my back and slipped back into my skin. I wanted to repeat this exceptional experience, but I failed to induce the state again.

[Salar de Uyuni] Salt flat reminds of a pavement made of huge salt stones

Suddenly, something tinkled on the road. I discovered that the magnet had fallen from the front wheel, and so the cycling speedometer was not working. Thanks to the transparent surface, I quickly found the lost magnet, repaired the broken loop with silver tape and continued on my way (I had a spare one anyway). Meanwhile, I noticed that the repaired front pannier rack was twisted, the weld severely disturbed, so I fixed it with bungee cords to prevent it from flying into the wheel when it finally fell off. It seems that an ordinary oxyacetylene burner is not adequate for welding aluminum. The salt brine on Solar de Coipasa considerably speeded up the whole process. But originally, it had looked promising. The connection was firm and that is why I did not leave straight away for Chile, but continued through to the Altiplano.

Incahuasi Island

This island is situated in the middle of the plains and is a prime tourist attraction. All tourist Jeeps stop there. Admission is 15 Bol. The whole island is covered in cacti and offers beautiful vistas of the wide flat white expanse. There is also a very basic accommodation facility for cyclists where I spent the night. One wall of the area was formed by a rock, the other by a Jawa 350, which was obviously still being used. Because I had decided to continue to Bolivia at the last moment, after welding the front pannier rack, I had not been able to replenish my stock of Bolivianos in Sabaya or elsewhere along the way. I began to have problems with cash and knew that I would not encounter any ATM in Bolivia again. So I managed to pay for my dinner in dollars. I took the front bag from the carrier, divided the cargo among the other bags and from then on continued on an asymmetrically loaded bike, with only the left bag in front. It took about a kilometer before I got used to it and adapted my cycling style to the irregularly spread weight.

[Incahuasi Island] Youth hostel for bikers; one of the walls is made of a rock

[Incahuasi Island] Llamas feed among the cactuses on the island

[Incahuasi Island] The island is approx. in the middle of Salar de Uyuni; the expanse of the flat is amazing

[Incahuasi Island] Picnic places for tourists in 4WD jeeps

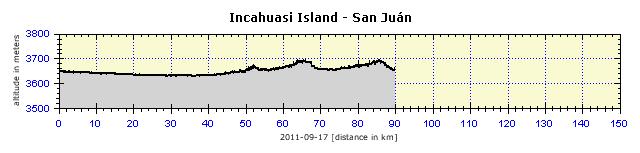

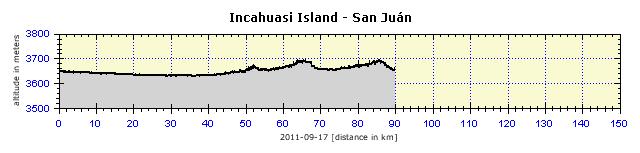

On the next day, I quickly covered just under 40 km on the southern edge of the plain. Then the typical Bolivian misery began – bad dirty roads buried in sand, while the sections without sand were corrugated. It is really bad to cycle on such a surface. One must employ a very technical style, it being necessary to remove the weight from the front wheel to prevent getting stuck in the sand. Nevertheless, I had to push frequently. In principle, I do not buckle SPD pedals to my shoes. In a skid, the leg goes down immediately, preventing the worst. Moreover, pedals processed by saline solution and sand are quite stiff. Even if spraying with WD, they would require thorough washing with WAP, which was not possible there. Water was in short supply. I guessed no one had WAP, and even if someone had it, the electricity was generally non-functioning. At the end of the day, I worked like a slave for three hours. I pushed the bike along the 11-km long road, buried under a 20-cm layer of sand and arrived at San Juán in total darkness (i.e. at about 7.30 p.m.).

[Road to San Juán] 20 cms. of fine sand: I “biked” 11 km in 3 hours; even pushing the bike was a real problem

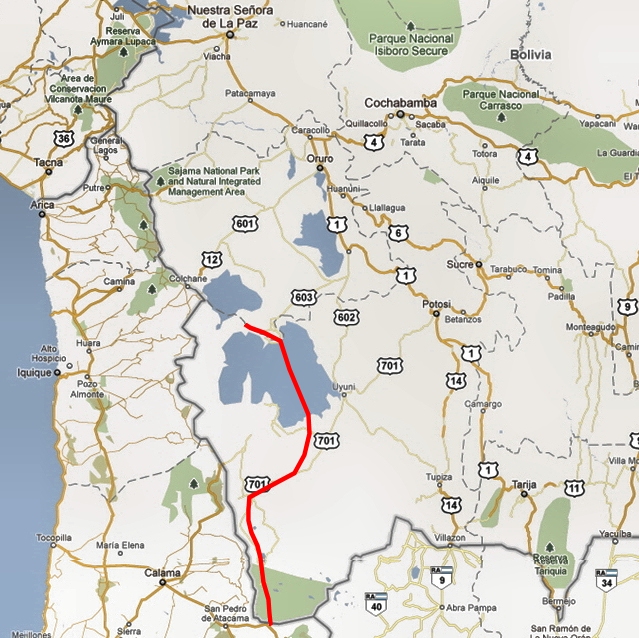

Tourists in Jeeps and Kings on Bikes

Local roads are passable only for top-quality 4WD Jeeps, with reduction gears and locking differentials. These 7-seater monsters are used by tourists for typical four-day trips, starting in the town of Uyuni, travelling mainly to the natural attractions of the South Antiplano and also to Chile’s San Pedro de Atacama. These tourist groups obviously have the pride and determination to undertake this adventurous route. Tour guidebooks emphasize responsible preparation, choosing the right company with quality vehicles and sober drivers who know all the dangers and tricks of the Altiplano. The adventurous nature of the tour is further enhanced by the miserable accommodation (even by Bolivian standards) in unheated, shaky buildings, where the only protection against the cold is a quality sleeping bag. And hygiene is also appalling – you can only dream of hot water. Running water is available only during the day, as it would freeze at night, and a flush toilet is also a device from the realm of dreams. Electricity works only for a few hours a day and is mostly produced by gasoline generators.

And now a crumpled and famished cyclist comes gasping into this environment, filled with adrenalin. Tourists suspect that it is probably not much fun to cycle here and show him real respect. On my arrival, they regularly applauded me. One young, beautiful lady even threw herself at me and hugged me, saying I was her hero. After I removed the ski mask from the bottom half of my face, and the helmet from my head, she found that she had hugged an old geezer who had not washed for three days and abandoned all further physical contact, but verbally insisted that she had meant what she'd said.

There are several communal pueblos where tourists sleep. One of these is the above-mentioned San Juán. I immediately found accommodation there and was the subject of the general interest of the tourists and even of their drivers, who discussed the details of my journey with me. Tourists get a pre-paid dinner, and of course I took advantage of the local kitchen and had a hearty dinner. Later at the Colorada Lagoon, I found out where the drivers ate and went there. An old woman had a simple stove with something resembling an oven in the middle of the room and was putting meals into the pots on the ground, doing everything with her hands without the use of a fork, even when placing the meat on the plates. Occasionally she, without asking, would throw a freshly baked piece of meat on to the plates of those who were already eating. And when someone did not eat everything, no problem, it was transferred on to the plate of someone else. But the diners were hearty. I was a distraction for them, an attraction. And my teeth still served me sufficiently to chew up even the leathery and stringy llama meat.

[Chiquana] The entrance to a pueblo; there is probably nobody there except soldiers

[Chiquana] Typical military igloos can be seen all around Bolivia

[Chiquana] After a half-day biking beside the rails, I finally saw a train

[Chiquana] A local cemetery

[Near Chiquana] White surface; Salar de Chiquana in the background

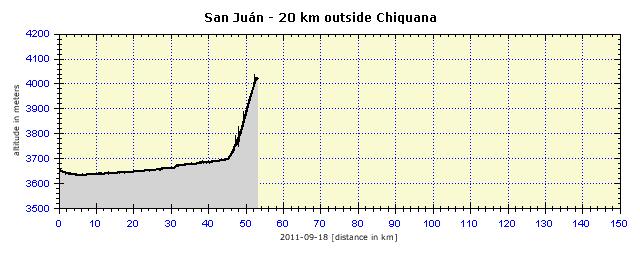

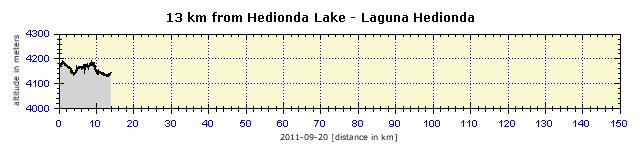

Suffering on the Way to Hedionda Lagoon

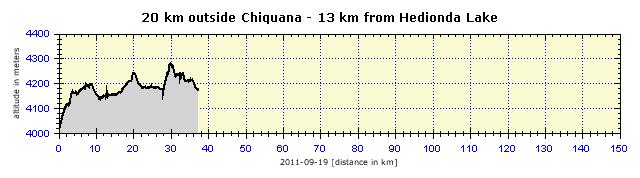

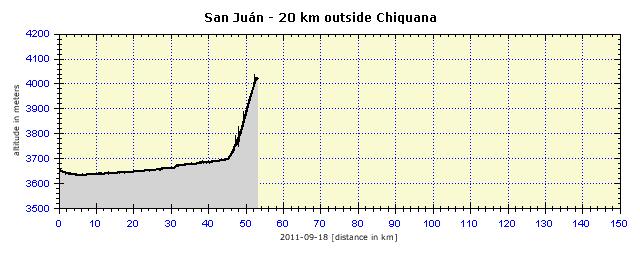

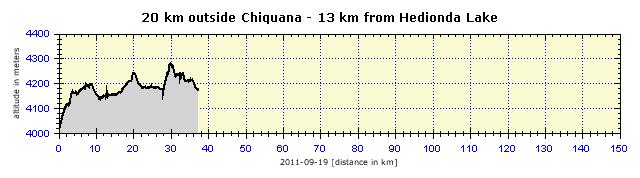

Then the worst part began for me. A sharp hill began after Chiquana in the rocky and sandy road and I alternately pushed and tried to cycle. In the evening, I flaked out on a hillside, hid myself in a creek from the razor-sharp wind and put up my tent. On the next day, like fata morgana, a good paved road appeared, leading from the Chilean border. With the wind at my back, I raced along it with such delight, that I forgot to leave it to take the dusty path 3 kilometers further on. So I had to go back another 3 kilometers against a strong wind. This put me back a little, in particular the contrast between the comfortable ride on the paved road and the inferno of the rocky path no-path. And so, even on the next day, I was not able to reach the lagoon and again put up my tent, this time on a small salt plain, about 12 kilometers from my destination. I had no water and so I waved at one of the last Jeeps. From their donated water, I could at least boil some soup (sardines and two buns in the morning, instant soup and the last bun in the evening). In the morning, I only had an apple, but I had accidentally left it outside in the bag and it was frozen solid, so I could only eat it just before noon.

Jeeps take the same routes, they circle the sights and places to stay, so they come and go in waves. For example, at around 10 a.m., about ten Jeeps rushed by in half an hour. Then all day, there were none until 4 p.m. when they returned, travelling in the opposite direction. I asked them for supplies only twice, once for the water and the other time for bread - I got 13 free fresh buns that lasted me for four days. But I do not usually resort to this tactic. One should be independent of passing motorists. Although, in this area, this is not entirely possible, and most cyclists I have read about have at least asked for some water. I had one advantage in that I was pretty fattened from home and so my body reached into its reserves stored in the “spare tire” around my waist and blew it right off.

[Near Chiquana] I appreciated every single piece of greenery amidst that tiring grey

[Near Chiquana] The Ollague Volcano in Chile dominated the landscape

[Near Laguna Hedionda] A pretty steep road up the hill plus headwind – I had to push the bike

[Near Laguna Hedionda] Bolivian Chiquana Volcano

[Near Laguna Hedionda] Overnight on a small 4180-m high salar; in the tent: 6 degrees below zero; in the sleeping bag: A1

[Near Laguna Hedionda] Tourist Jeeps can be seen from a distance, giving themselves away by the dust clouds

[Laguna Caňapa] Series of lagoons begin here

[Laguna Caňapa] Flamingos didn´t like my interest so they swept nobly out

[Laguna Caňapa] Flamingos “interposed” with flying birds

[Laguna Hedionda] The lake has a large population of flamingos

Hotel Los Flamingos

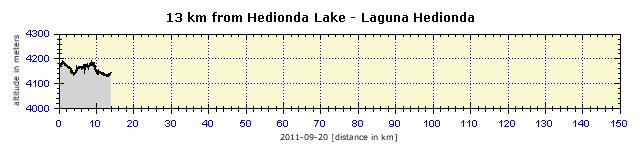

After two days in the tent, starving, unwashed and covered in omnipresent dust, I desperately needed food and a shower. There is an expensive hotel, Los Flamingos, at the Hedionda Lagoon, which has an outstanding view of the flamingos on the lake from the dining room window. The price of accommodation starts at USD 85, but they took pity on the poor cyclist and accommodated me for USD 25 with breakfast. I was the only guest anyway. I had a wonderful hot shower, which is unique in Bolivia. Never in my life had I taken such a long shower. I washed my clothes, hanging them out in the wind, so that they dried quickly. I sprayed and oiled the bike, scraped off the salt (without water). I had a good dinner. Except for biscuits, they had no food for sale, so in the morning I ordered six hamburgers to somehow survive for the next two days without catering. After all, stopping Jeeps and begging for food seemed cowardly to me.

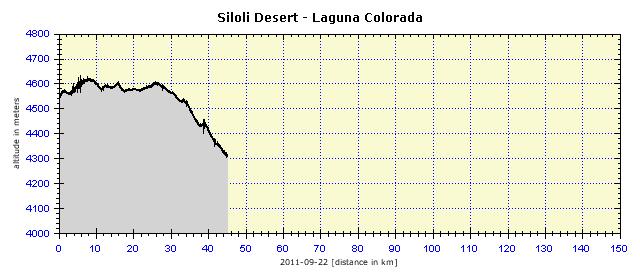

I was totally exhausted, so I checked if there was any way to shorten the route, cycle around Chile, etc. No way! Once you get here, there is no alternative, you have to complete the whole trip properly. And I already knew that there was a desert awaiting me, and then an uphill climb almost into the clouds. It was sometimes so rough that I was happy when I managed to cycle and walk 35 km during a whole day.

[Laguna Hedionda] Los Flamingos hotel

[Laguna Hedionda] The place with a great many views

[Laguna Hedionda] Los Flamingos Hotel situated on the lagoon bank has a lovely view of the flamingos

[Laguna Honda] The morning ride around the lagoons was pleasant; the usual sweat came later

[Near Laguna Hedionda] The road went higher and higher

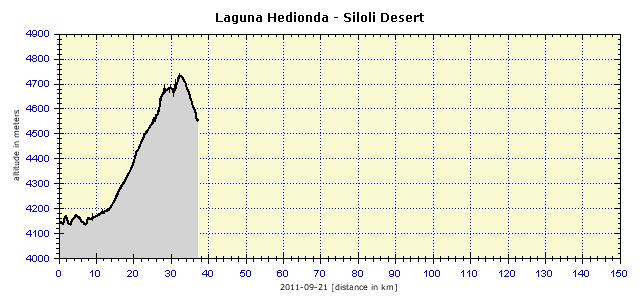

The Dreaded Siloli Desert

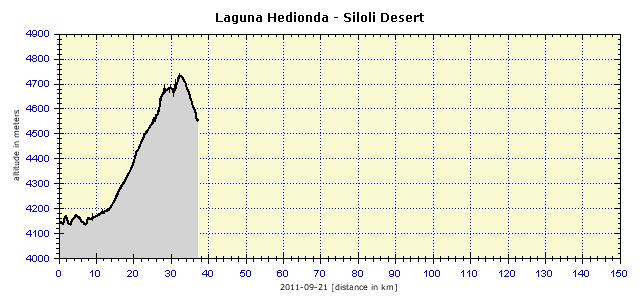

I slept in the tent on the edge of the desert and, in the morning, was curious to see how I would fare. For the first half-hour, the surface was frozen and cycling was possible, but then the wheels started to sink in and the fun was over. I was seized by skepticism, which rarely happens to me. I would have to push the bike all day in that killing wind. I would cover maybe 20 km before I could put up my tent in the frozen desert, to go to sleep, hungry until the morning. And no one would help me. The Jeeps full of tourists had no vacant seats, so nobody would offer me a ride. I was fed up, I felt the altitude (I was at 4,500 meters), I was losing balance on the bike, simply a psychic breakdown. Then I found, by reaching into my right pocket, a forgotten bag containing pieces of coca leaves. They were already pulverized, but should still take effect. I swallowed in order to have some saliva in my mouth, put the three pinches of coca powder into my mouth and processed the leaves into a compact mass with my teeth. Then I inserted it under my gum as a proper bago. And it really started to work. Altitude problems vanished, my mood improved significantly and, when pushing the bike, I rested less often than before. Then I saw a Jeep on the left side of the plain, so perhaps there was a road. I pushed the bike through sand for about 2 km and indeed, there was a path, uneven and buried in sand, but still passable by bike. A strong wind blew at my back, atypically raging already from the morning (usually it started to blow at about noon). So I really enjoyed the ride.

[Near Laguna Hedionda] Overnight in the Siloli Desert; the billboard partly protected me from the strong icy wind

[Poušť Siloli ] Strange icy objects shaped by wind

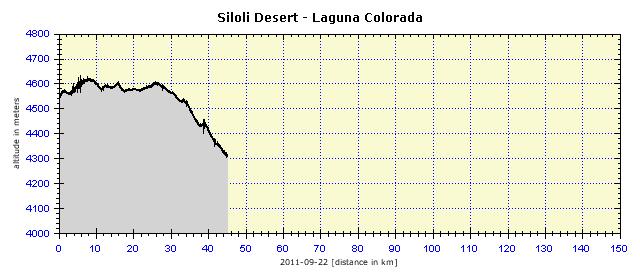

Miracles do Happen

After about an hour, I saw a vehicle coming from the opposite direction. I did not pay any attention to it, as I was busy choosing the right track on the road. One always tries to find an optimal path, changing trails, to find in the end that it is actually “lo mismo” (the same). However, the vehicle was driving very slowly and its shape was unusual. And when it got close, I thought, "Hell, could it be that, really, yeah, it must be a SANDPLOW, Madre Mia, a real PLOW and plowing the path through the sand!" When it approached, I danced an improvised Thanksgiving Dance for the driver, and he laughed like crazy (I've always had two left feet when dancing). My situation improved 100%. The route was beautiful, the storm was at my back. It was a completely relaxed and easy ride. Yet there were sections where the wind managed to cover the road with sand again in less than two hours after the passage of the plow. At Arbol de Piedra (a rocky formation in the shape of a tree) the adjusted road ended, but it went downhill to the Colorada Lagoon, which eliminated the worst road. The lagoon reflected a deep red color with white edges, a pleasant sight from the distance. There is the entrance to the National Park at the lagoon where I was deprived of 150 Bol., so my financial situation worsened considerably again. At the worst, I still had dollars, but generally, there were infinitely few opportunities to buy anything.

[Poušť Siloli ] Miracles do happen – a plow coming from the opposite direction

[Poušť Siloli ] On the left: original state; on the right: the road flattened by the plow

[Poušť Siloli ] Arbol de Piedra, or rather, Stone Tree

[Laguna Colorada] The white colour by the coast, the red colour in the middle

[Laguna Colorada] The red colour in the middle part of the lagoon is very unusual

[Laguna Colorada] Flamingos do well here

Pull over a little more, Dude!

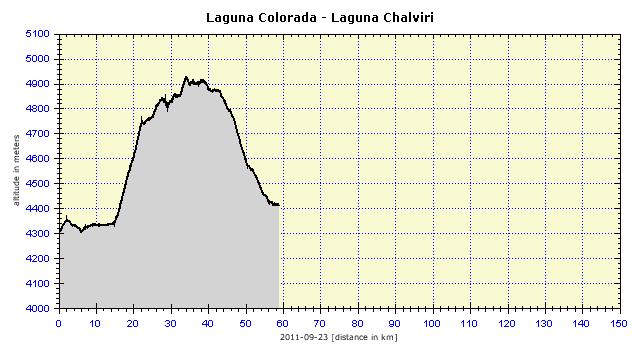

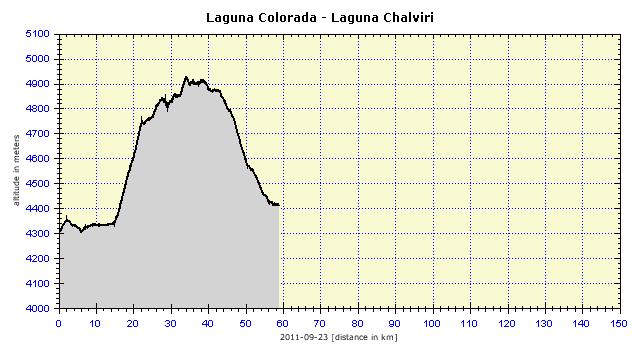

This rather frightened me. I had to cycle up to the Sol de Maňana geysers, which are situated at just below 5,000 meters above sea level. I got up very early in the morning, had a stringy llama steak, bought from an old lady feeding the drivers, and headed off before 8 a.m. The first 20 km were on flat uneven road covered with sand, and then it came. The steep dirt road demanded heavy pushing on the pedals. However, it was surprisingly good with a minimal layer of sand. One could always cycle on one or other side of the road. I had easy gearing, but pushed hard on the pedals because I did not want to sleep over in the tent at such an altitude. On the height graph of the GPS I found with relief that I had already done half of the climb, but I had crossed the line with some effort and was quite exhausted. I was hungry, ate a few biscuits but that did not help. Once again, the coca saved me! I mined the remaining crushed leaves, made two bagos and cycled like a rocket. I finally reached the height of 4,920 meters, a record I will probably never again break in my life on a bike.

[Near Laguna Colorada] Unusually good-quality road for Bolivia, with steep gradient

[Near Sol de Maňana] 2 more km before I reached the highest point of the journey

[Near Sol de Maňana] GPS shows my new altitude record

Bolivian Rotemburo

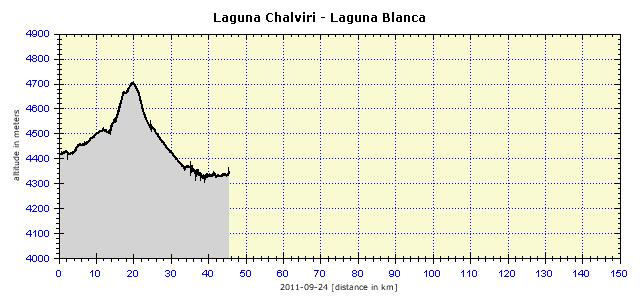

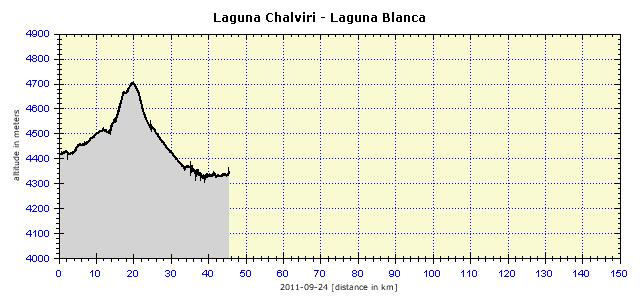

A wild, approximately 22-km long downhill road to the Chaviri Lagoon followed. The wind blew hard, although from behind, but this only worsened the situation. On the road covered in sharp stones I had to apply the brakes and choose the best path to avoid a puncture. We pros do not carry spare tires with us. Just before sunset, I reached a natural hot-water pool where there was a large dining room. They did not have accommodation, but when I said that I did not need a bed, they offered me sleeping space on the floor in a corner of the dining room. The condition was that in the morning at 6 a.m. my bedding was to disappear, because tourist Jeeps would be arriving for breakfast and a morning bath. And they gave me a cup of coffee. I discussed with the lady what she would cook for my dinner. Her husband and his friend called me from the pool to come and bathe. It was as cold as a morgue outside, my teeth were chattering as I changed into my swimsuit in the house next to the lake, but the swim was amazing. 35°C warm water flows into the lake, so there is no need to wash before jumping in. Bright, clear stars overhead, all the fatigue of the day just disappeared. I recalled the Japanese onsens (spa) where there is always some rotemburo (outdoor swimming pool). So I told this to my companions in the pool in my stumbling Spanish and said that indeed they were cooperating with the Japanese.

[Laguna Chaviri] The guys already waiting for me in the hot-water lake

[Laguna Chaviri] The owner – a nice guy - let me stay overnight in a corner of the dining room

The Last Tremors

Then I already knew the worst was over and that I would be on the Chilean border the next day. In the morning, I managed to tidy up everything, put the bags on the bike and went to breakfast as if I had arrived just before the tourists. I headed off at 7 a.m. and it was incredibly cold. After 2 km my hands in the neoprene gloves were frozen (I had bought the gloves from a Japanese Army surplus store somewhere in Hokkaido), so I threw the bike down beside the road, put my hands into my armpits, and started running around in the road, screaming in pain, tears coursing uncontrollably from my eyes. When my hands had defrosted, I stuffed the double Alpaca woolen gloves, which I had bought providently for a few bucks in La Paz, under the neoprene. The road rose steadily during the morning. I was quite exhausted after the previous day, but more especially as I had not expected this. The psyche is the basic thing. So I pushed the bike for about 3 km up the steepest hill. I did not mind, I had enough time to finish the trip. That is why I did not even use the remains of the coca. I cycled between the Verde Lagoon (which is green, with the Chilean volcano, Licancabur, in the shape of a regular cone, towering above it) and the Blanca Lagoon. I reached the border of the National Park, opposite the Ranger's house. There was an accommodation facility where I stopped. Everything in the hostel was as is standard in Bolivia – no water, no electricity, ugh toilets, bare wiring in the bedroom. A hot shower was science fiction, so I washed myself in cold water taken from the barrel used for flushing the toilet. I arranged with the caretaker about what she would prepare for my dinner. After dark, the generator was turned on for two hours, the light did not work in my room, so I moved to another. The power supply from the wall outlet did not work, but the batteries could run for two more hours, so I wrapped myself in two blankets and, wearing my favorite hat of Alpaca wool, wrote this diary entry. The old woman stood behind me for half an hour, watching me writing. I had the impression that she was seeing a laptop computer for the first time in her life.

[Laguna Verde] Green water rippled by wind; with the Licncabur volcano in the backround

[Laguna Blanca] The “neighbour” of Laguna Verde framed by Bolivian mountains

Lessons from a Crisis

I have to admit that the Southern Antiplano was the most difficult terrain I have ever cycled in. Terrible roads, terrible vertical distances, demoralizing wind, very limited possibilities of supplies, eternal dirt, sand everywhere, relentlessly burning sun all day, severe cold in the evening and at night. And especially the altitude, which in my opinion takes away at least one-third of one’s performance. It was on the edge of my ability, but I MADE IT.

Recapitulation – broken front pannier rack, I was cycling with only the left bag; shorts torn in several places (cycling shorts for 75 USD did not last for 2000 km, bad cut and bad fabric – producer: German firm ONLINE, I patched them up with silver tape); frozen fingers with deep painful cracks in the skin; legs battered from the pedals during frequent bike pushing; chronic cough and almost non-functioning SPD pedals gummed up with salt and sand that resisted all attempts at cleaning. Really fun.

P.S.

What I wrote about levitating in Salar de Uyuni was completely fabricated. You do not have to believe all the bullshit...

|